Saving the Winged Mapleleaf Mussel from Extinction

This summer, on the banks of the St. Croix River, a team of experts took important steps forward

to help save a federally endangered species from extinction.

The Wild Rivers Conservancy, and multiple federal, state, and university partners committed resources, expertise, and time to preserving one of the only known self-sustaining populations of the winged mapleleaf mussel (Quadrula fragosa). Mussels have long been a valuable resource, both ecologically and culturally, in the St. Croix and Namekagon Rivers. Each of the 41 mussel species found here today was present in these two rivers before European settlement. Today, this remarkably diverse mussel community is a rare example of an intact group of river-dependent animals that has withstood the test of time and changing environmental conditions. However, five of these mussel species are now considered endangered.

The winged mapleleaf mussel is one of those vulnerable species. Once thought extinct, a small population was discovered in the St. Croix River in 1987. Though other winged mapleleaf populations have been found in some waterways in Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Missouri, the St. Croix River population is genetically distinct and the only one known to be reproducing. Finding these mussels meant not only a chance for one species to be restored but also the opportunity to maintain the rare species assemblage present in the St. Croix River. While the existence of this reproducing population brought hope, the complex life cycle of freshwater mussels meant that innovation would be necessary to achieve a stable population.

Freshwater mussels have a complex life cycle that depends on a host, often a fish, for microscopic mussel larvae, or glochidia, to develop into juvenile mussels. In early fall, female winged mapleleaf mussels display a tissue lure to attract a host fish, and in the St. Croix only the channel catfish will do. The glochidia released by the female mussel then attach to channel catfish gills where, over the next 7-8 months, they develop into juvenile mussels. Those juvenile mussels then detach from the host fish and fall to the riverbed as free-living mussels.

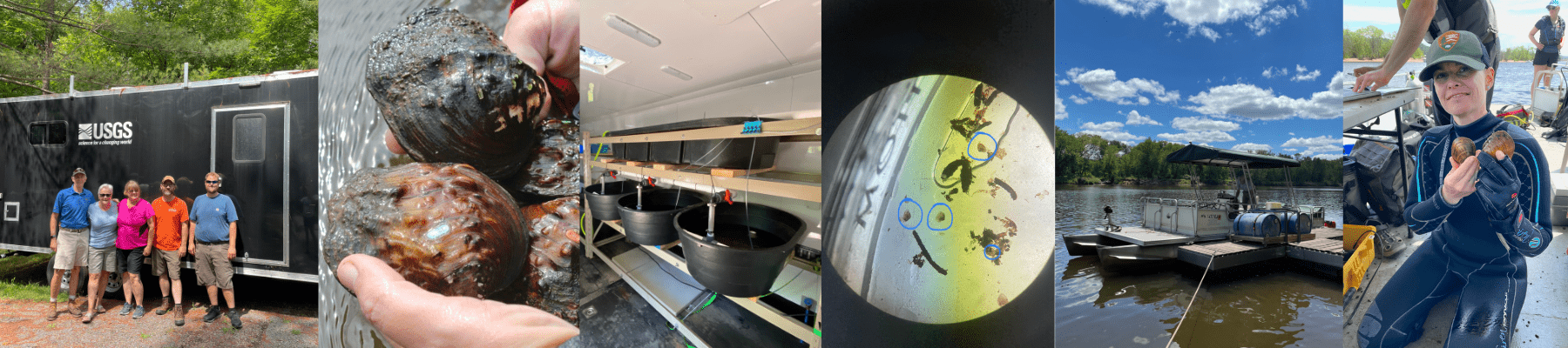

Over the past 17 years, efforts to propagate winged mapleleaf in hatchery and laboratory facilities have been limited due to high fish mortality overwinter while glochidia are attached and from high mortality of newly released juvenile winged mapleleaf held in the laboratory. The Wild Rivers Conservancy began partnering in 2021 with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and National Park Service, St. Croix National Scenic Riverway staff to determine an optimal environment for successful survival and growth of propagated juvenile winged mapleleaf. While the propagation efforts in 2021 provided lessons and insights, 2022 yielded more promising results. In spring 2022, approximately 3,600 microscopic juvenile winged mapleleaf that released from channel catfish overwintered in USGS ponds in La Crosse, Wisconsin, were moved to tanks in a USGS trailer along the St. Croix River and supplied with river water. By fall, 102 of those juveniles had grown large enough to be seen with the unaided eye. With guidance from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, these juvenile mussels were placed in the Riverway and are now the first propagated winged mapleleaf mussels to overwinter in the St. Croix River since 2005.

At this point you might ask “why should I be concerned about mussels?” While freshwater mussels are seemingly sedentary, they are valuable “ecosystem engineers.” Unseen beneath the water, mussels are hard at work modifying aquatic habitats by removing contaminants and harmful bacteria, algae, and potential toxins, excreting nutrients that become available food resources for plants, fish, and other aquatic insects. Although they have persisted for millennia, mussels, such as the winged mapleleaf, are sensitive to environmental changes. Like a canary in a coal mine, their health can reflect the health of the water bodies they inhabit.

The St. Croix River project is part of a larger plan of the Mussel Coordination Team that includes federal, state, and non-governmental partners working to protect and restore endangered mussels in the upper Midwest. You can be a part of this ongoing effort to protect this federally endangered species and other native mussels. While transporting watercraft in the Riverway, practice “Clean, Drain, Dry” to prevent introduction of invasive species such as the zebra mussel. Remember, it is illegal to take any live mussel or empty mussel shell from the St. Croix and Namekagon Rivers. Even moving a mussel is prohibited because it can suffocate if put back incorrectly.

To learn more about the winged mapleleaf propagation project, view the Conservancy’s Lunch and Learn webinar, Saving the Winged Mapleleaf Mussel from Extinction, on our YouTube channel.

Looking for your own wild adventure? Visit our events page for adventures

with our experienced and knowledgeable team.

Photos by Greg Seitz, Chris Barnhart/Missouri State University, National Park Service, and Wild Rivers Conservancy