“Many of us breathed a sigh of relief when the Lower St. Croix River Act was signed into law,”

U.S. Senator Walter Mondale told a gathering of national leaders in 1974. “That reaction was premature.”

A barebones document, the Lower St. Croix River Act of 1972 required additional appropriations before it was close to fully implemented, and it was another four years before the formal protection plan would be approved by the National Park Service. In the meantime, the nation was riveted by the Watergate hearings, Gerald Ford replaced Richard Nixon as President, and development pressure along the St. Croix loomed large.

When the dust settled and the Lower St. Croix Master Plan was completed in 1976, community and government leaders had a new cooperation-based toolkit for protecting the lower St. Croix River’s astounding scenery, clean water, and ecological values. In the years since, those tools have served the river well overall--though not without conflict.

A Unique Cooperative Model

The lower St. Croix is not a national park like Yellowstone or the Grand Canyon. The National Park Service owns very little land in the lower Riverway other than a few islands and instead manages hundreds of conservation easements placed on private lands to protect the river’s scenic and ecological values.

While the National Park Service manages the upper river and the lower river through Taylors Falls, Minnesota, the final 27 miles of the St. Croix is managed by the Minnesota and Wisconsin Departments of Natural Resources. That means the health of the St. Croix depends on cooperation between the states, the many towns along its banks, riverfront landowners particularly those with easements and river users.

Steve Johnson, whose long St. Croix career began in 1977 at the now defunct Minnesota-Wisconsin Boundary Area Commission, saw this model of cooperation in its earliest days. “Local governments were starting to say ‘no’ to some developments or trying to figure out how they could say ‘yes,’ and the state agencies were stepping in to help them interpret the ordinances,” he said. “Part of my role was to help the local government think about their decisions with respect to what was going on with the other side of the river. There was a lot of hand-holding and telling people, ‘You need to do the right thing.”

Protection Wins and Losses

Molly Shodeen, widely recognized as a crucial “riverkeeper” for the St. Croix in her 36-year career with the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, knows how the river would look if every proposed riverfront development had been built. “All you have to do is look at the Mississippi River through St. Paul to imagine what the St. Croix would have looked like,” she said. “It would be wall-to-wall condos and apartment buildings because the view would have been monetized.”

“The cooperative management agreement for the lower St. Croix has been an effective forum”, she says. “The opportunity is there to work together and a lot of times it succeeded--you can pull out success stories where there was a partnership and you got decisions that were made for the greater good.”

Rules for Responsible Boating

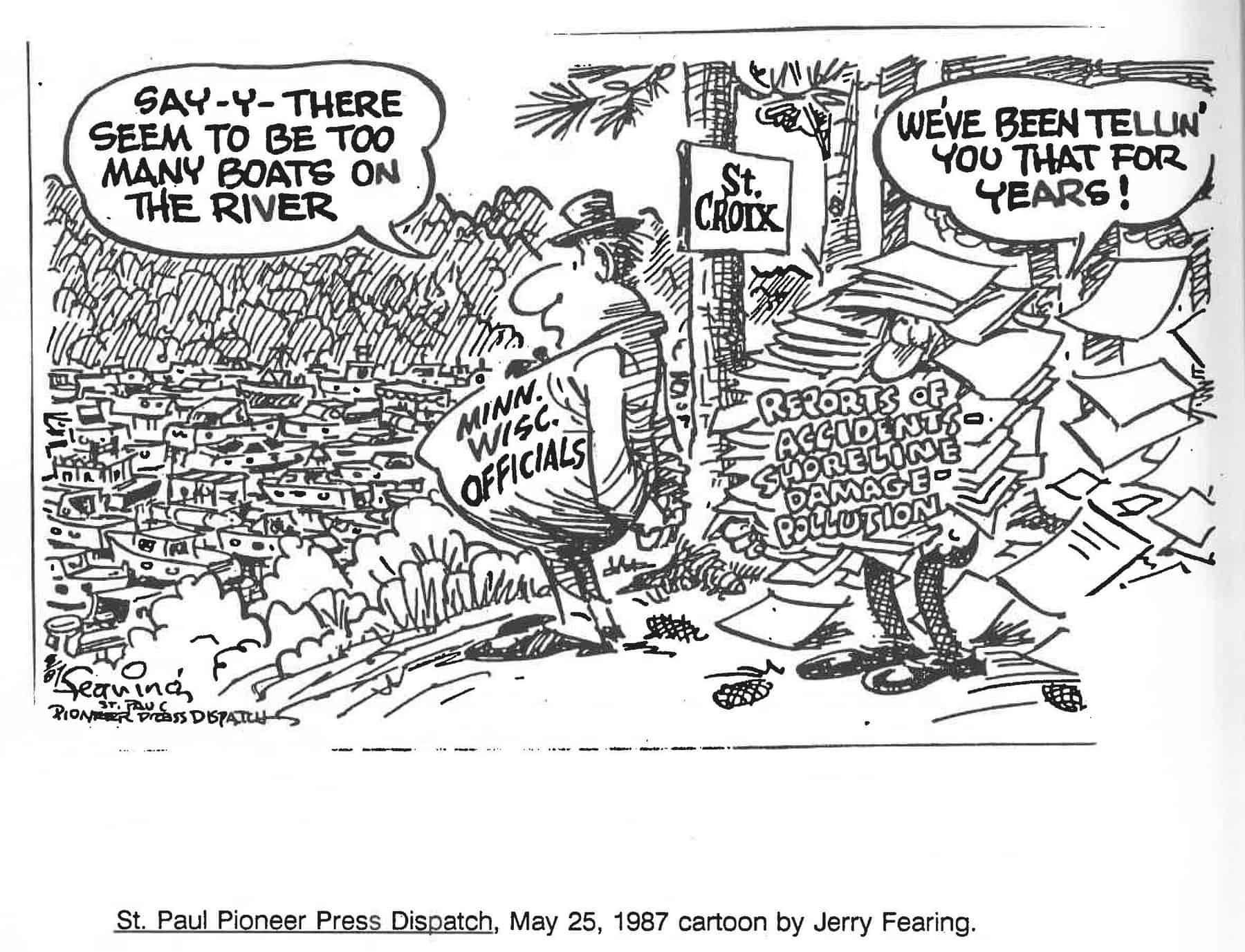

In addition to protecting scenic views, the lower St. Croix’s designation also spurred regulation of on-water activities. The Lower St. Croix Cooperative Management Plan, completed in 2002 through an intensive community process, shape the boating regulation including prohibition of airboats, jet skis, and other personal watercraft north of Stillwater, a slow speed requirement north of the Arcola bridge, and a no-wake requirement for the entire lower river during periods of high water.

“We spent many meetings talking about boat speeds,” remembers Randy Thoreson, who served as planning coordinator working for the National Park Service. “It was controversial but it stands the test of time. Our shorelines would be trashed and we would be doing a lot of shoreland restoration now if it wasn’t for that cooperative plan.” Boating rules for the Lower Riverway can be found here.

An “If Not For” Tour of the River

Long-time river champions can name exact places that would be different if not for the Lower St. Croix Act and the state and local regulations that followed. Steve Johnson remembers multiple massive hotel and conference centers proposed along the lower St. Croix, including one with a planned “sky bridge” over Highway 95. There was also a time when the City of Hudson sought a new industry, rather than parkland, along their stretch of riverfront. Some proposed projects over the years conflicted with the river’s Wild and Scenic designation but were made better by the influence of agencies and river advocates.

In the final installment of this series, we will take a close-up look at some of the places with close ties to the Lower St. Croix Act.