If you’ve spent time exploring the St. Croix, you know our cherished river possesses two distinct valleys.

The upper river is narrow and winding, with whitewater rapids and dense forests. The spectacular rocky gorge of the Dalles, straddled by the towns of St. Croix Falls and Taylors Falls, marks the start of the lower river, which gradually widens into an opulent, pastoral landscape before broadening further into Lake St. Croix below Stillwater and joining the Mississippi River.

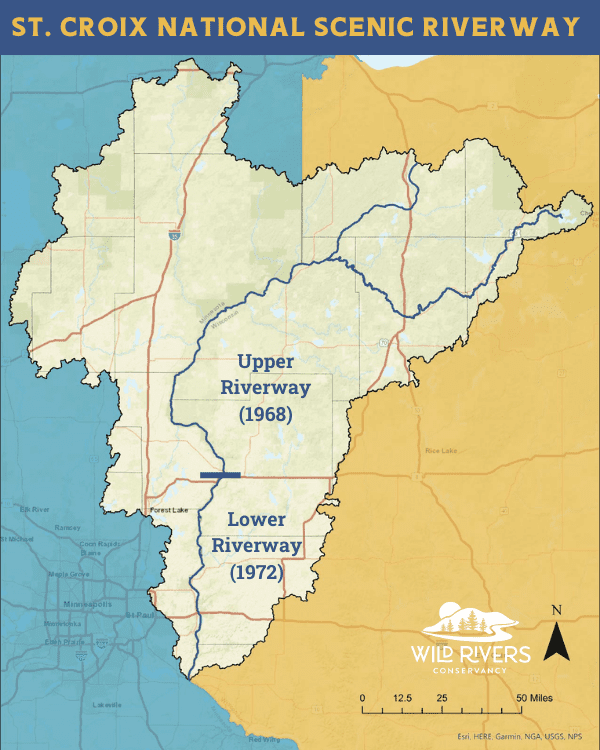

The lower river is breathtakingly beautiful, but it was left behind in 1968 when the upper St. Croix was designated a National Wild and Scenic River. Four long years of advocacy and negotiation succeeded in protecting the lower river in 1972, which is why we are celebrating its anniversary this year. But why wasn’t the St. Croix protected all at once? Here are four reasons the upper and lower river stories diverge.

Geologic Forces Set the Stage

Generations of geology students have flocked to the St. Croix, particularly the Dalles area with its distinctive rock formations that can be traced to a failed continental rift near Lake Superior more than 1 billion years ago. Massive ice sheets later moved through the area, melting to create ancient lakes—the rushing waters of Ancient Lake Duluth shaped the upper river while Ancient Lake Grantsburg is thought to have overflowed its banks near what is now St. Croix Falls, helping to carve the wider lower valley we know today.

When the glaciers retreated, the upper river emerged with sandier soils that came to support pine barrens and mixed hardwoods while much of the lower river valley was blessed with fertile soils and habitat that still supports a high diversity of aquatic life, including rare species.

Historic Land Use Reinforces the Differences

Archeological findings tell us that human occupation of the St. Croix Valley began some 10,000 years ago. Dakota and Ojibway tribes lived and traveled along the river for centuries and remain active in the valley community today. As French voyagers arrived in the 1600s, fur trading patterns divided the valley with the upper river ultimately dominated by Ojibway and economically tied to Lake Superior and the lower river home to the Dakota and linked to St. Louis-based traders.

In 1837, after a treaty now recognized to be extremely unfair to native people, loggers surged into the valley to cut the vast hillsides of white pine—coveted as “perfect for building.” Over the decades nearly seventy dams changed the river’s flow as billions of logs were floated downstream to busy sawmills in the new towns of Stillwater, St. Croix Falls, Marine, and Hudson.

The logging industry largely moved on by 1914, leaving the valley’s hillsides devastated. The swift currents of the upper river inspired Northern States Power to acquire nearly 30,000 shoreline acres on the St. Croix and Namekagon for potential hydropower projects, and a second-growth forest sprang up on its banks. In the lower valley, fertile, rolling hills attracted farmers who removed tree stumps to grow wheat and other crops. Gradually, a new ecological chapter began on the river.

Location is Everything

Flash forward to the St. Croix in the 1960s. Minnesota’s Twin Cities, less than an hour from the lower St. Croix, had become a booming population center with nearly one million residents. East metro industries—and new highways—were contributing to urban sprawl making a beeline toward the lower river. City dwellers moved east, seeking their own slice of paradise, and marinas and parks grew to provide boating, swimming, fishing, and other recreation opportunities like never before.

Development pressure was building at breakneck speed and leaders were concerned that the St. Croix might become, in the words of Wisconsin Senator and Earth Day Founder Gaylord Nelson, “just another urban river whose values have been squandered.” Something needed to be done to protect the St. Croix before it was too late.

Popularity is a Blessing and a Curse

The upper St. Croix, with its rapids, sandy soils, and location farther from population center, was only minimally touched by development in the years following the logging era. Meanwhile, the broad placid waters of the lower river valley, its fertile pastoral landscape, and its location close to growing urban centers combined to make the lower St. Croix very popular.

As federal leaders surveyed rivers for inclusion in the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act underway in 1968, they determined that the lower river was, in fact, too popular and was already starting to be developed. Despite the best efforts of local, state, and national champions led by Senator Nelson and Minnesota Senator Walter Mondale, only the upper St. Croix was protected that year; the lower river was excluded. But all was not lost. The official recommendation read:

“The St. Croix River…(below Taylors Falls) is a recreation resource of outstanding quality, even though development precludes classifying it as a wild river. Appropriate measures should be taken to assure perpetuation of this portion of the stream as a recreational resource of high quality.”

Lower St. Croix leaders took this declaration as a challenge and committed to protecting the full St. Croix as soon as possible. How they achieved that protection, four years later, will be the subject of our next blog post.