When the United States Congress passed the 1968 Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, the near-pristine upper St. Croix was among eight treasured waters “instantly” protected. The lower river from Taylors Falls, Minnesota to its confluence with the Mississippi River at Prescott, Wisconsin was excluded by a small margin, at the last moment. But it did win a consolation prize.

The lower St. Croix was deemed a river “to be studied” for future protection. Lower river conservationists had a foot in the door, and a new chapter of the St. Croix protection story began, complete with cliff hangers, shifting protagonists, and a backdrop of ideological struggle for the future of the country.

Studying Becomes an Action Verb

The Study Team created to decide the lower river’s fate included a combination of state leaders and federal officials, some of whom began the process with little knowledge of the St. Croix and very high standards for the type of nature warranting federal protection.

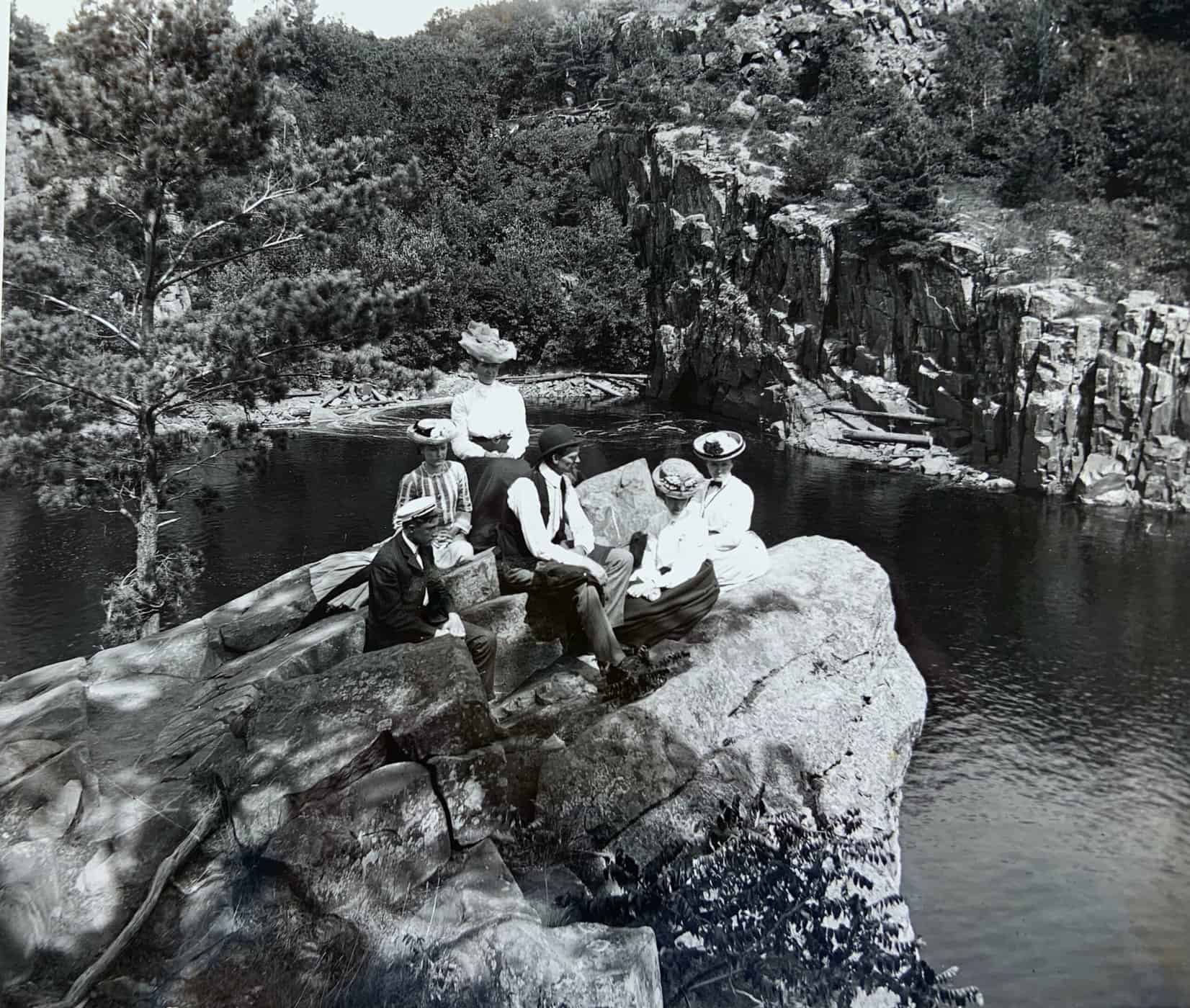

Boat trips to the Dalles left agency officials astounded by river’s grandeur—but as they moved south, the marinas, boat traffic, riverfront cabins and islands littered with trash had others wondering if the lower St. Croix had already been spoiled by overuse.

As the Study Team worked toward a determination, questions about federal versus local control, funding mechanisms, and protection strategies blossomed into disagreements. In a move fit for a reality TV show, the National Park Service backed out of the study process at one point in 1970 after hearing about the project budget, claiming to be “fed up with trying to do the job we are charged to do and at the same time lack the kind of program support we need to do our job.” When the federal Bureau of Recreation’s river-supporting director was replaced by notorious anti-environmentalist James Watt, the prospects grew darker.

In June 1971 the Study Team released its recommendations, suggesting a combination of federal and state protections for the lower St. Croix. But the Department of Interior fought against this plan and others were concerned about protection strategy details. All the while, river advocates who had packed public meetings, testified, and written letters making the case for lower St. Croix protection, confronted new threats.

Intensifying Pressure Spurs a Congressional Solution

When the St. Paul-based Calder Corporation proposed to construct multiple ten-story high-rise condominiums on the bluff in Hudson, Wisconsin, the people who lived along and cared about the St. Croix were dismayed. As one activist told the Minneapolis Tribune, the proposal “put everybody on notice that this place was up for sale and it was going to the highest bidder.” This extreme threat to the river also galvanized support for protection. Fortunately, Minnesota Attorney General Warren Spannaus intervened to stop Calder‘s financing plan that halted the project.

Fearing that time was running dangerously short for the lower St. Croix, Minnesota Senator Walter Mondale and Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson, came together to introduce federal legislation before it was too late. “The crush is on,” Senator Mondale said of the intense development pressure building on the lower St. Croix, “and unless we can protect it some way, it’s going to go.”

The Department of Interior continued to fight against federal protection of the lower St. Croix, but the winds of change were blowing. In a 1972 environmental policy statement President Richard Nixon highlighted federal support when he pledged that “the need to provide breathing space and recreational opportunities in our major urban centers is a major concern of this administration.”

“Outstanding bipartisan achievement” Saves the Day

Senators Nelson and Mondale, now joined by Wisconsin Congressmen Vernon Thompson and Minnesota Senator Hubert Humphrey and Congressmen Joe Karth and Albert Quie, brokered a deal with the National Park Service that also had full-throated support from Minnesota Governor Wendell Anderson and Wisconsin Governor Patrick Lucey.

The lower St. Croix would be protected through a combination of federal and state cooperation, with the National Park Service administering the “scenic” 27 miles from Taylors Falls to Stillwater, and Minnesota and Wisconsin jointly administering the “recreational” section between Stillwater and Prescott.

The Lower St. Croix Act, signed into law in October 1972, declared that the river and its immediate environment possessed “outstanding scenic, esthetic, recreational, and geologic values and should be protected for the benefit and enjoyment of future generations.” Congressman Quie said it was “nothing short of a legislative miracle” and Governor Anderson summed up the campaign as “an outstanding bipartisan achievement.” The Minnesota and Wisconsin Legislature passed companion legislation the following year.

An Ending that is Also a Beginning

Passage of the Lower St. Croix Act sounds like a happy conclusion to the lower St. Croix protection story. But the devil is in the details and the language in the Act was not very detailed. Implementing the new bill, including creation of a master plan, would be a much greater political and administrative challenge. That story will be the focus of our next blog post.

Information and quotes from this story are drawn from “Saving the Saint Croix, An Administrative History of the Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway” by Theordore J. Karamanski.